issue 7 FEATURE

iNTERVIEW

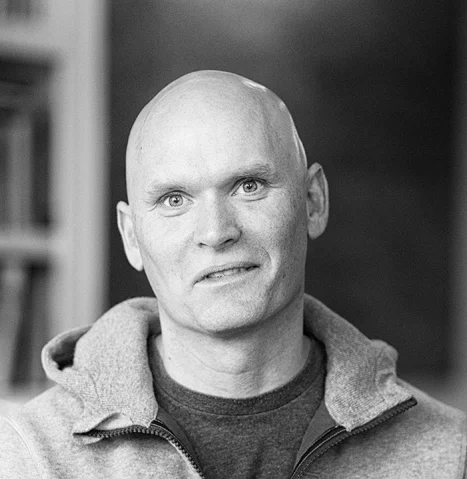

Anthony Doerr

The following interview was conducted by Nicole Cullen in Boise, Idaho. Mr. Doerr kindly invited Bat City Review’s fiction editor into his office, a room decorated with children’s drawings and punctuated by an oversized easy chair. They talked about writing, research, travel, and fur trapping over turkey sandwiches.

Nicole Cullen

What was the first book that influenced you as a writer?

Anthony Doerr

The C.S. Lewis books, The Chronicles of Narnia. My mom read them to my brothers and me and the books blew me away. I remember I kept asking her how they were made. How did these people make this world? It was so intoxicating—the idea that with these cheap materials you could generate elaborate pictures in someone else’s mind. It really sounds like magic when you put it like that. There’s something magical about trying to make up stories and using language to do it.

Nicole Cullen

Did that spark your interest in the fantastic?

Anthony Doerr

It’s a little uncomfortably nerdy to say I’m interested in the supernatural. But yes. I was raised Catholic, and I was going to church hearing about some dude raised from the dead. We were surrounded by the supernatural in a very mundane way. There’s all this magic being pounded at you, saying this is real, this is real. Part of it was being raised with a religious belief around me, whether or not I was assuming it myself.

Nicole Cullen

Your writing showcases an intense curiosity for the world at large. How do you negotiate which subjects to write about? How does an interest in, say, seeds or cone shells or cranes translate into characters?

Anthony Doerr

It’s really hard to say why you’re curious about something. The world is absolutely, stunningly amazing. Whether you believe God made it or evolution has delivered us into this moment in time, you have to appreciate the luck of being here in this one moment. I think for some reason I’ve always had this strange, early sense of mortality, and in some ways that makes you an anxious person, and in some ways that really liberates you, too. I think about death a lot, and I think about how short our lives are—in geologic time in particular, we're just a blink of an eye.

The fact that my job allows me to go learn about forest fires or seeds, and really use narrative to investigate these curiosities—I love that. I feel blessed and lucky to be given the chance to learn about anything I find interesting. But of course to get readers interested in those things, we need narrative. Just like religion, like what we were talking about—we need story and character.

I start with something I’m really interested in. For “The Hunter’s Wife,” it was ladybug hibernation. What do bugs do through the winter? Can you say they’re dreaming? Certain frogs thaw out and live again—what do you call that? Is that life or is that death? Maybe death isn’t a sudden switch that’s thrown, but maybe there’s this large area of dreams between the two. There’s something beautiful about that. It can take me years or months or sometimes weeks to build characters up from that. So often for me, it’s falling in love with the language around a subject. There’s a whole language that spirals up from shells—the ramps and spines and whorls and folds that people talk about. I fall in love with the poetry of these things. There’s always some kind of implicit human metaphor, and I’m always fumbling after that.

Nicole Cullen

Let’s talk about place. Your settings span the farthest reaches of the globe—from South Africa to Germany to Wyoming. Can you talk about travel and how it influences your writing?

Anthony Doerr

Traveling is a way to see things with new eyes. Not only to see where you’re going but where you’re coming from. It sounds cliché, but I think it’s really true. I grew up in Ohio, and I always wanted to leave, always had maps on the walls. My first real trip I took a semester off from college and went to Kenya for six months. When I came back everything looked different. I remember going to the convenience store and looking at all the drinks. Why do we need so many drinks? In Kenya you can choose Coke or Fanta. Traveling helps you understand where you come from. But more than anything, it helps you crack apart that skin that forms over your eyes. When you’re in one place all the time, things start to become invisible.

Tolstoy has this cool line in his journals—something like if you dust a couch but you don’t really remember dusting it five minutes later, it’s as if you never dusted it. He extrapolates it to say if whole lives go on that way, it’s as if those lives never existed. I think what he’s saying is that art exists to wake you up. And for me, travel and art are linked in that way. Leaving home exists as a way to wake you up as well, to see what you take for granted.

Nicole Cullen

Research. How much do you pull from outside texts, how much from your imagination and your own experiences?

Anthony Doerr

For me, research is fundamental. But imagination is a big part of it. And travel, too. Research is not just sitting around reading books necessarily. It’s Googling the parts of a snowmobile, or whatever you need to know to get the fiction plausible, to get the authority that you need to be an author. But more so it’s to investigate curiosities. I write about science for The Boston Globe, mostly because it feeds my fiction in these really interesting and tangential ways.

It’s about being comfortable enough and being confident enough. Often I get nervous and I get sick and it’s because I’m thinking about myself. And that’s not a healthy place to be. If your eyes are open upon the world, there’s so much to see and learn from it. That’s why I like to travel—you get to a place where they don’t speak English, you’re uncomfortable, your eyes are wide open and you’re seeing what’s possible. And you feel so alive. Translating that into language is pleasurable. And that’s why I write, to translate the world into sentences. To share an appreciation of it.

Nicole Cullen

Are you going to these places with a story in mind, or are you getting there and starting fresh?

Anthony Doerr

Both. In the best-case scenarios, I’ve been there before, then set a story using photographs, journals, the Internet, and books. Then I go back once it’s mostly drafted. About Grace: I had lived in Alaska three summers before, and I had a bunch of journals from which I could steal, say, the way a sky looks. Then I’ve got it. I can cannibalize it, and then once the book was drafted, I went to a hotel and worked for two straight weeks. I don’t like being away from home too much, but then I could double-check the facts. That way you don’t lose your authority.

Nicole Cullen

The stories and novellas of your latest book, Memory Wall, are deeply concerned with time and history, permanence and impermanence, and the seeds of memory. How do you balance plot, character, and metaphor? Do you feel it come together organically when you’re writing, or do you work at it through revision?

Anthony Doerr

I have to work at it. It can be miserable. Some days are really hard days and I think this thing is intrinsically flawed and will never come together and I have just wasted five months of my life and I have to go face my family and tell them that I suck. It’s the worst. So, no, it doesn’t necessarily come together organically, though you desperately want your reader to think it has. You want to erase all the blood and the nails and the struts that go into your work.

Nicole Cullen

How long did it take you to put together Memory Wall?

Anthony Doerr

It took four years. I wrote parts of Memory Wall in 2005. The title story took me six months, and I worked every day straight. Occasionally, I’ll take a break and write newspaper reviews for money, but I work five days a week.

You read through the stories for the hundredth time, and you try to figure out how to make them work together. At one point I was on the ground trying to piece them together, trying to figure out the order, how to go from seeds in “Village 113” to “Procreate, Generate.” I wanted to ask questions of the reader and also the writing world. Can you write a story collection that is not just linked through characters or setting? I thought it would be interesting to write a story collection that is more like a suite, arranged neurologically, thematically, around a single question. Or maybe it’s a bunch of houses built around a central courtyard, which is memory, and these are bay windows that look out onto that same courtyard. In my favorite story collections, like Ship Fever or Jesus’ Son, the thread goes beyond common settings or characters.

Nicole Cullen

“Afterworld” is told from the point of view of an old Jewish woman whose seizure-induced visions evoke memories of her childhood. I read somewhere that you came across a list of Jewish orphans while doing research for your forthcoming WWII novel. Can you talk about that?

Anthony Doerr

Yes, I was looking through stacks of deportation manifests, these meticulous records that were kept of extermination, essentially, and the people who were deported from cities in Germany and sent to Auschwitz or Treblinka. I don’t remember exactly why, but one of the manifests caught my eye. It was a list of girls’ names and birthdates. All of the birthdates were 1928 or later, so the oldest person was 16. I thought, what is the story behind this thing? That stuff literally takes your breath away. And that’s tied in with your research question. This is real. There’s something so awful about the fact that this was so real and so relatively recent. I pinned it up to my bulletin board and tried to figure out how to make a story about that. I feel like it has everything to do with memory.

WWII is becoming a video game. The History Channel is all good-versus-evil and battle reenactments. It’s like, we got the Germans! And that’s okay if it stimulates people’s curiosity about WWII, but WWII is becoming history and not memory anymore. So many people are dying every day for whom WWII was memory. And you have to be really careful in that gray period when veterans are dying. History can be controlled and changed so quickly by people in power, and you have to say, can I reinvest in the personal histories of people even if they’re fictional? I feel like that’s a moral act too, somehow. You try to do the right thing by saying these are the lives and I can tell you about these lives in detail and maybe they will feel real to you again so you can understand the horror of what was going on not so long ago.

I was reading an Oliver Sacks book where he talks about TLE [temporal lobe epilepsy] and how you can have these visions that feel entirely real, but are also filled with dread and often come over you out of nowhere, in the middle of a conversation, where you’re seeing ghosts, or some kind of color, or smelling certain smells. So I thought, okay, that’s interesting. I was riding my bike to work, and this moment came over me: the afterworld is a white house filled with thistles, or something like that. Okay, so what is that? Maybe I can make a story out of that. Maybe an epileptic is seeing that. I don’t want to say to the reader, this is the afterlife. It’s just one person’s idea that maybe this could be the afterlife, because she [Esther] has a real reason to believe it might be. She wants to believe that these girls aren’t gone forever. [Doerr pauses and laughs.] It’s so awkward to talk about!

Nicole Cullen

Can you tell us more about your new novel?

Anthony Doerr

I’m working on a novel about a 12-year-old blind girl in WWII France. It’s about the use of radio, and subversively passing messages against the Nazi occupation. Right now I alternate between her story and a German boy, trying to braid their stories through short chapters. I told myself I’ve got to get it in by December, because I really want to write a book about Idaho.

[Doerr reaches into a brown paper bag.] This is a beaver plew! This thing is so cool. Cort Conley gave it to me. He’s in touch with all these trappers. I said, “Hey Cort, I’m thinking about writing about fur,” and four days later he’s dropping off two full boxes of books at my house. I’m very interested in the idea that people came out here for reasons that can ultimately be traced back to fashion. It wasn’t so much westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. The fashion in the 1830s surged an interest in beaver skin hats. I want to write a novel about one trapper and somehow juxtapose that hard living with glamorous fur parties, set around the 1830s, when we turned the West into a fur desert, eliminating populations of animals.

Nicole Cullen

How do you juggle being a husband, father, and writer?

Anthony Doerr

I have an office. That’s a huge thing. Shauna’s with the kids right now. No matter the ages of your kids, you always feel guilty. It was really hard when they were babies because there’s so much hard labor involved. It’s like, okay, I’m going to go write now, and your life is going to suck for a few hours, and I’m going to pretend to write, but really I’m going to fall asleep. That was my life for the first year. I had to relearn what it was like to be a writer. Marriage is a totally different thing before and after you have kids. It should have a different name. We had two right away and we have to negotiate a lot of things. Suddenly your self isn’t as important as the two little selves you’re trying to keep alive.

We moved to Rome the first year, and it was us against the world. We didn’t even have a bench; no one was coming in off the bench to help out. That was great for our marriage and made us better friends, but in the beginning the boys were up every night, and I was supposed to be thinking clearly enough to make stuff up in the morning. I could see my wife thinking, I can’t breastfeed these two all day, good God.

I was just trying to learn how to write again, but I was also falling in love with Rome at the same time. There are stories on every street corner. Here in Boise, a century home is a big deal—you get a plaque if your home is 100 years old. Big deal. Our Rome apartment was 500 years old, and that’s a young apartment. It was hard to juggle. Mostly I was in this dream of being a new parent in this new country and trying to go back to what I had been doing.

I kept journals. I didn’t know it was a memoir [Four Seasons in Rome] until long after we’d been back. I’d written a lot about the pope dying, and I got more e-mails for that than other magazine pieces. I thought, maybe people are interested in this—one person’s view of this media circus around death. And then an editor wrote and asked if I’d ever thought of making it into a book. But also I wrote to prove to myself that what we had done was real. You come back here and everything is really familiar and easy. I thought, did we just do that?

Nicole Cullen

When did you know you would make a life of writing?

Anthony Doerr

I was always very shy about writing. I would never suggest, say, to my mom that I wanted to be a writer. But I think being the youngest kid helped. You know, my brothers could be more serious. I thought if they got real jobs then I wouldn’t have to. The expectations were different. I was shy about saying I was a writer even after my first books were out. You sit next to a stranger on an airplane and they ask what you do and you say you’re a writer. They want to know what your books are about. Have I heard of them? I still say I’m a teacher sometimes. It’s strange to hear people talk about your career as a writer. In another sense, part of the reason I live here is that I’m not surrounded by the competitiveness of writing, and I can surround myself with it as much as I want by reading, and not as much by the literary party scene. When I go out on the weekends, I’m with a dentist, a doctor, a broker, and a guy who owns a golf course, and I like that.

On the other hand, when Saul Bellow dies it’s nice to have someone to have a beer with. It’s nice to know there’s someone else out there taking the same risks with his or her own life. To know that there’s someone out there making up stuff in a room, that’s good to know.

Almost 400 people came to my reading when Memory Wall came out. I’m always surprised by their thrill of having me here—especially when I’m hung-over at the Co-op on Saturday morning. Boise is a beautiful place to live. If you want to get in the hills, you can. Yesterday I was on the South Fork of the Salmon River fishing into the evening, and that night I was reading to my kids in bed. We didn’t see a soul up there—four miles of river without seeing another human being all day. I say crank up the drawbridge and keep them out!

Nicole Cullen

Okay, last question. Why do you write?

Anthony Doerr

The greatest gift we have as writers is that we don’t have to go spend a shitload of money doing it. The raw materials to write a book—a pen, a ream of paper—cost about five bucks. There’s something so democratic about it, and I love that. That goes back to what C.S. Lewis could do. I haven’t even read those books for quite some time. But the idea that he could give me visual images and also olfactory and auditory senses, he could work on me as a kid. And he’s dead. He’s using these really cheap materials to do it. That’s a great skill and I hope that people keep reading books for a long time and I think they will. And libraries exist where we can go in them and get this shit for free!

Reading is a kind of transportation. My favorite books are the ones that utterly transport me somewhere else, into someone else’s life. They make you feel un-alone—David Foster Wallace said reading makes you feel un-alone—and that’s exactly it. You can fully enter another person’s consciousness, as fully as we can hope to, through reading. Reading teaches you to go beyond the self, and that’s something I feel really strongly about. Even as we’re sitting at our desks writing alone, we’re actually exercising a great act of empathy, trying to enter another person and explain that we have commonalities. I feel like that’s the one thing I can give my students—what you’re doing is actually probably the most important thing.

Fiction can make the strange familiar to you. It can bring strangers to you. It’s so important—and now more than ever, as we drop bombs on people by remote control from Virginia—to understand that other people laugh and cry for the same reasons that we do, and that’s what fiction can do, even more than cinema and playwriting. It is a kind of prayer or practice. That’s the goal of my life. My life is boring, and I want to keep it that way. I want to use fiction to explore other lives, and that’s why I read, too. Not to escape, but to understand. If I’ve learned one thing so far, it’s this: you don’t write what you know, but to know.

Anthony Doerr is is the author of the story collections The Shell Collector and Memory Wall, the memoir Four Seasons in Rome, and the novels About Grace and All the Light We Cannot See, which was awarded the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.